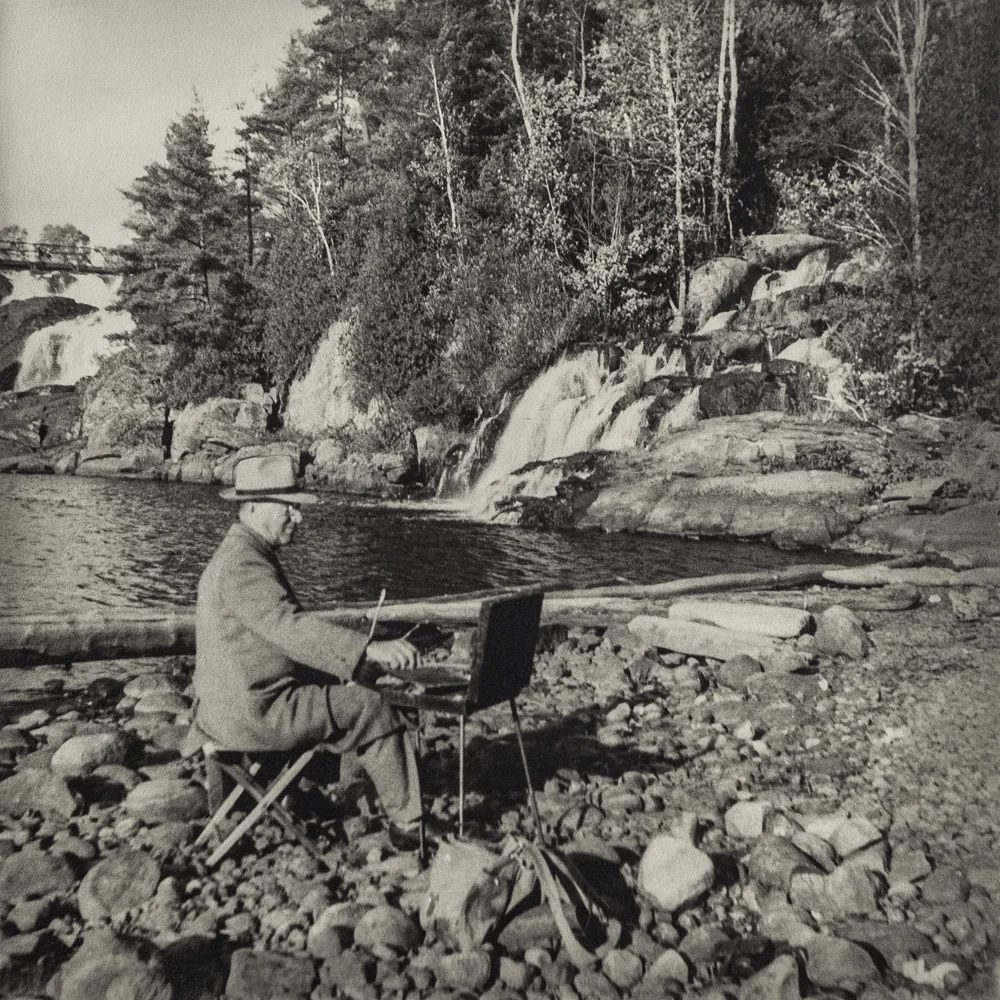

On Peter Clapham Sheppard RCA OSA (1879–1965)

By Louis Gagliardi

And that things are not so ill with me and you as they might have been, is half-owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

Peter Clapham Sheppard had lain in an unmarked and unvisited tomb for over fifty years in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto, until last fall when I arranged to have his name and dates finally inscribed on his headstone. Once done, on a late morning in October, I returned to his resting place to observe the moment in private and solitary ceremony. That visit, I knew, also commemorated an emotional milestone at the end of a thirty-year-journey for me as, just as those newly engraved letters marked his place among the unremembered dead, a book was at that moment in the hands of a publisher that would restore the artist’s name, his life, and his art to the public. It was an instant like no other, and one that I will take with me at the last hour, along with the constant comfort of a purpose fulfilled, a promise kept, and gratitude for the transformative power of having lived with devoted passion——there on that October morning, in the solitude and silence broken only by the soft commotion of chill-bitten leaves.

This is the story of three lives and of three different generations beautifully intersecting one another through Art over the span of a tumultuous century. It is a rich and “embroidered ribbon” that unspools artfully as a novel or a work of cinema; rich with “wonder and woe, glory and grief,”and beautifully illustrated in high-resolution with the stunning visuals of rediscovered artworks, most of which have been unseen for the greater part of a century. As a story it is the conjunction of Thomas Gray’s Elegy and Howard Carter’s discovery in 1922; that is to say, it is both a reflection on the forgotten as well as the ecstatic recovery of lost treasures.

It begins with Peter Clapham Sheppard whose life at age sixty unfolds into a new destiny when he meets Bernice Fenwick Martin, 38, who in turn enters my life in the last chapters of her own to transform all three lives, completely, with powerful joy, purpose, and resolution.

A précis, at least my version of one, would go like this:

Sheppard, born in Toronto in 1879, becomes a protean talent in early twentieth century Canadian art, specifically during the 1910s and 20s. He is a modernist, exceptional with the urban as well as the northern landscape. In 1941, at the funeral of J. W. Beatty in Mt. Pleasant cemetery, he meets Bernice Martin, also a former student of Beatty’s at the Ontario College of Art, a printmaker and painter who is a generation younger. The two would spend the next twenty-four years inextricably bound by creativity, companionship, and ultimately love. Sheppard’s last years of penury and oblivion are solaced by Bernice, his last friend and support. At the end of his life, she places him in the care of the Salvation Army Lodge on Davisville Avenue with the added consolation that, this way, he was literally only steps away, that is, across the street from the Millwood Avenue home that she shared with her husband Langton. When Sheppard died, he left Bernice the only asset he had: all his artworks, a lifetime of his artistic legacy, wherever they might be found.

In 1971, as I lay in bed and looked out the window to a patch of starry night, just as Proust once dropped a madeleine in his tea to experience a seismic effect which recaptured the past, Don McLean’s homage to Van Gogh played on the AM radio beside me and in that moment set the course for my future. It was just as Graham Greene so artfully phrased it in his masterwork “The Power and the Glory” when he wrote, “There is always a moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” What followed was a monomania for Vincent Van Gogh and the lifelong pursuit of consolation in art, poetry, music, and literature. It determined a course of study in Art History at Western University and heralded a lifelong journey of limitless joys among which this book is now counted. In many ways, my entire adult life has been spent looking out that window from 1971.

In 1987, I saw a painting in a gallery which delighted me but about which I knew absolutely nothing. “It just spoke to me” as the saying goes. A name and address on the back impelled me to get in my car to meet the artist. It led me to the Salvation Army Lodge and Bernice Fenwick Martin. When she first appeared, I saw a petite woman of gracious and dignified mien with a hint of the glamour of a bygone gilded age, like that woman in the Klimt painting. I could not know it then, but this countenance belied her tragic ruin and fall from “riches to rags” as she would often say later. Having been defrauded and dispossessed of her home, her wealth, and all her possessions years before, including the Sheppard estate of artworks, she had been doomed to repeat the very fate as the man whom she had housed in the same building decades before when at the end of his life he too was poor and alone, but for the solace of her friendship. The poignant irony to this chapter is that, located in the very small bedroom to which her world had now been confined, a window looked out to the very house and happy life she once knew and lost, a cruel and painful daily reminder, there across the street on Millwood Avenue.

I began to regularly visit Bernice at the Salvation Army and soon the humanity of her story and condition cemented a friendship, despite the fifty years that separated us in age. We shared a bond of the highest and rarest kind——the love of Art: one having lived the active life of creativity; the other, the student of art history with a romantic spirit guided by a love for Van Gogh, Tennyson, and Thomas Wolfe.

Over time the story of Sheppard and Bernice’s loss induced a common purpose that rejuvenated us both. In the process, she became freed from the charitable shackles of the bank and trustee and regained a sense of autonomy and independence. I helped her find an apartment in a seniors’ building that restored to her a freedom and a pride of place. We set about to reclaim whatever artworks by Sheppard we could locate, although hundreds of sketchbooks, oil panels, and canvases had been lost, stolen, and sold off in bulk containers at garage-sale prices at an estate sale over which she was utterly powerless. It was at one location, on such a quest of her direction, that our hopes were initially dashed until, by dint of physical exertion on my part, a cache of these wondrous artworks by Sheppard revealed themselves in the dank and dingy darkness of this space. The shock of juxtaposition between beautiful artworks and the chaos of the surrounding detritus was not lost on us and I will never forget the gleam of discovery in her eyes at that precise moment when, upon opening the flaps of a cardboard box, we first glimpsed the gem-like painted surfaces of the cigar-box panels painted by Sheppard and now featured on pages 70, 71 of the book. It was that expression of speechless joy on Bernice Martin’s face when we looked at each other by the light of a handheld flashlight that will be with me at my last breath. In that instant she was reunited, not only with the man she loved and admired, but with the legacy he had left her, out of love and friendship and gratitude. It was as though all the preceding years of waste and loss were suddenly redeemed and fresh hope restored.

Many of the paintings had suffered decades of distress and oblivion, but they are here now, and for future generations, and they sing triumphantly in the pages of this book.

The friendship between Bernice and me transformed our lives. For her last twelve years of life, she was loved, enjoyed the company of my family at holidays, delighted in my mother’s Neapolitan cuisine, and felt inspired by the dreams of the son she never had. Bernice Fenwick Martin passed away on September 15, 1999, just months before seeing the new millennium and two years shy of reaching her hundredth birthday. As for me, she gave me the ultimate gift through her friendship and faith: a purpose which became the validation of a life and identity that began with that song for Vincent long ago, when in my bedroom staring at the night, my future took its first breath.

A Master Rediscovered

The Sheppard Project

In the following section I will address three questions that sum up this project to which I have devoted the last thirty years.

1. Who Was Sheppard?

2. Why Don’t We Know Him?

3. Why Should We Be Excited About Him?

Peter Clapham Sheppard c.1929-1930 in his Toronto studio. The paintings Louisa Street (Left) and Seaport (Right)

1. Who Was Sheppard?

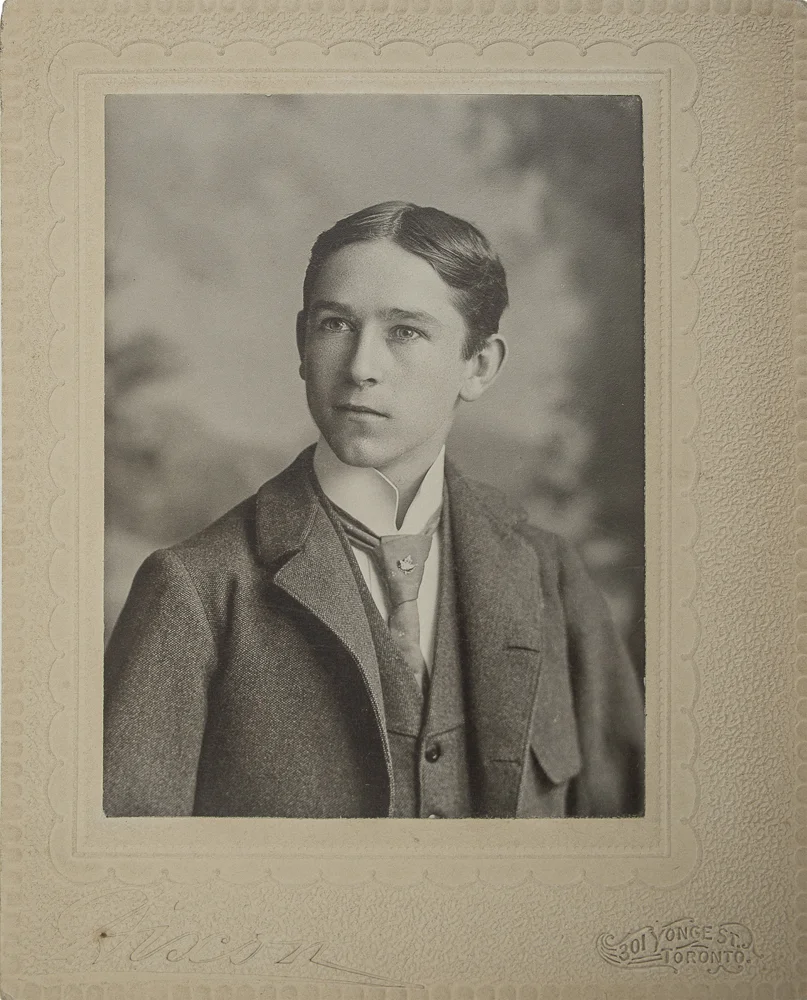

Born in Toronto in 1879, Peter Clapham Sheppard was a master draughtsman, lithographer, and consummate painter whose contribution to early twentieth century Canadian art has been forgotten. As a student at the Central School of Art and Design, later instituted as the Ontario College of Art, Sheppard’s education was steeped in the precepts of the academic tradition taught to him by George Agnew Reid and J. W. Beatty.

Indeed, the purity of Sheppard’s early figurative works attest to this: the ease with which he rendered light, form, and space earned him distinction for which he was awarded the Sir Edmund Walker Scholarship and the Stone Scholarship. Sheppard’s early works, like those of his peers in Toronto, reflect the various stylistic influences that were imported from Europe from waves of Canadian artists who had studied overseas since the 1870s. Academic painting began to be challenged by the new “modern“ approaches evidenced in the subjective naturalism of the Barbizon School of landscape artists (1830–70); the Impressionists; the monochromes of The Hague School; and Whistlerian tonalism. Many of these developments in art were highlighted in the works of artists who formed the Canadian Art Club in Toronto and who exhibited annually there from 1908 to 1915. As Joan Murray writes in her book, The Birth of the Modern: Post-Impressionism in Canadian Art: [Re: The Club] “In its early shows, the paintings displayed were often restrained in colour and atmospheric. By 1912…the exhibitions were dominated by Impressionism” (p. 14). And a little further she states that “By 1913, Post-Impressionism was coming to broad public consciousness in Canada” (p. 15). Even decades after the emergence of modernism and the European models which Sheppard and others emulated during these early years of the twentieth century, audiences here would have witnessed the defiance of tradition in the intense and arbitrary use of colours, the importance of strong contours, the bold brushwork, and abstracted forms. In Sheppard’s alignment with the New York collective known as the Ashcan School in the 1910s, his choice of the modern city and its common people lived up to the principle of the earliest pioneer of modernism, Baudelaire, whose dictum to the artists of his day was il faut être de son temps. Wedded to these artistic developments in Toronto was the growing self-conscious expression of national sentiment, a Canadian point of view, the “first potent stimulus” of which “came about in 1893 at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago,” according to C. W. Jefferys in a letter to William Colgate, which I chanced upon in the Archives of Ontario [F1066]. Exhibited there were works by Scandinavian artists whose landscapes and climates reminded the young Canadian men in attendance of their own country.

By 1911, Sheppard’s status in the Toronto art scene was established. In a photograph of that year, published in the Toronto Star Weekly under the caption “Exhibitors of the OSA”, (p. 55 of the book), he stands in equal fellowship with the best artists of the day, from the old guard to those of his generation, some of whom would form the Group of Seven later on in 1920.

By 1912, he, Lawren Harris, and J.E.H. MacDonald are at the foot of Bathurst Street painting the gritty industrial site called The Gasworks. In the next few years, Sheppard will take his modernist ambitions to record the dynamism of the modern cities: Toronto, New York, and Montreal. In his total devotion to the aesthetic of drawing and painting, he will immerse himself as a spectator of the urban experience, create records of his times, and by stopping time, leave us with these beautiful intimations of immortality. The artist rests in peace. His art lives on.

1879-1965

The artist rests in peace and his art lives on.

Represented Canada on the world stage at Wembley, Great Britain - 1925 and Exposition D’Art Canadien, Paris, France. - 1927

2. Why Don’t We Know Him?

My obsessive fervor over the last thirty years has been an attempt to bring to public attention artists, such as Sheppard, unfairly erased from history due to the brand that was and is the Group of Seven. In his 2006 book, National Visions, National Blindness, the late Professor Leslie Dawn wrote: “A mandate to underwrite a unique national art founded in landscape and paralleling that developed in England appeared as soon as [Director Eric] Brown took office at the National Gallery of Canada [1912]. From this moment, he took a concentrated interest in the painters who would later officially form the Group of Seven in 1920. Despite claims in the conventional narrations of the Group’s history that its members faced opposition and neglect before being vindicated, they were, since their first appearance, the handmaidens of the NGC and consequently of the state, in the birth of this identity invested in the visual arts” (p. 11). A great country such as ours cannot and should not limit its art history to the uncritical praise and recycling of ONE overreaching narrative. And in the current era when the humanities have been devalued and business schools have invaded university campuses, those liberal traditional bastions of arts, letters, and critical thought, more and more young Canadians learn less and less about culture and specifically their country’s art history. The gatekeepers of our visual arts and the elitist merchants who have traded and profited in status symbols need to encourage and fund a new generation of Canadian art historians and scholarship. I’m not only speaking for Peter Clapham Sheppard here but for all the other women and men who were written out of history and “now rest in unvisited tombs.”

3. Why Should We Be Excited About Sheppard?

What we have before us in the Sheppard archives is a truly rediscovered legacy of an unknown but important Canadian modernist working in the early twentieth century and whose works offer us a fresh and dynamic alternative to the Group. It is plausible that it is the last preserved critical mass of museum-quality artworks by one historical artist not in a public collection. Most of these beautiful works of art have not been seen in a century.

As Canada’s identity evolves it’s important to keep history in our ongoing conversation: to teach us; to guide us; to uncover new knowledge; and to enrich our present. Sheppard’s rich artistic output, at least that part which has been salvaged along with acquisitions made along the way, offers us a keyhole to our past, richly preserving a collective memory as only art can.

In an artless world of mass-cultural overload, his works offer us, as they have for me over the years of changes and tragic loss, the consolation of beauty and the pointing gently toward a higher consciousness.

Thank you.

Devoted Friends:

Bernice Fenwick Martin (1902-1999) and P.C. Sheppard strolling the grounds at Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto.

Bibliography

Dawn, Leslie. National Visions, National Blindness: Canadian Art and Identities in the 1920s (UBC Press, 2006).

Gay, Peter. Modernism: The Lure of Heresy from Baudelaire to Beckett and Beyond (W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 2008).

King, Ross. Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven (Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, 2010).

Murray, Joan. The Birth of the Modern: Post-Impressionism in Canadian Art, c. 1900–1920 (The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa, 2001).

Smart, Tom. Peter Clapham Sheppard: His Life and Work (Firefly Books, Toronto, 2018).